German cartes from the 1900s

“There are no facts, only interpretations.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

The idea that there might have been something called a unique or native German photography doesn’t get much attention until the 1920s when an essential form of modernism took off in the Weimar Republic. Until then German photography is regarded as a variation on a general European theme, but around the very end of the 19th century German studios began producing portraits that are so distinctive you only have to glance at one to know where it came from. One of the keys is the tonal range; muted greys are preferred over the contrasts of black and white. Another is the colour of the card mounts, olive, drab brown and pearl grey replace the cream of earlier times. Dimensions matter too. Once CDVs and cabinet cards came in standard international dimensions. Now studios begin utilizing card sizes with specific names: the Mignon (45x67mm), the Melanie (90x120), the Promenade (105x210) and so one, some 40 that are officially recognized above what studios came up with on their own. This portrait of a woman is a classic example. Actually it is a standard cabinet card but you know at once it comes from Germany, or at least the Germanic speaking lands east of France. It is also (speaking relatively here) very modern. You would say at once that it was taken sometime around 1910. Partly it’s her expression, which admittedly isn’t that vivid but rather more subtle than earlier photographers would have been allowed, and one reason for that is that it is obvious she is being lit by electric lamps. Historians might dither over where to place it on the timeline. Is it a remnant of 19th century portraiture, Pictorialist or early Modernist? We don’t have to concern ourselves with such details. It is enough to look at it to know it is good.

Going back a few years, we have a typical example of an1870s CDV. It could have come from anywhere – France, the US, Australia or even Turkey. It is a rather excellent study of a boy but the most interesting part may be that it was taken in a studio belonging to Anna and Minna Kohnke, in Mehlbye, near Kappeln, close to the border with Denmark. Studios run by women weren’t unusual, just uncommon, but Mehlby was just a village. You feel there is more to the story of Anna and Minna Kohnke but what exactly that is remains unknown for now.

Moving on to the turn of the century and another portrait that could come from just about anywhere, which doesn’t detract from its quality. Some people might be drawn to the tow boat, the fake rock or the boy’s sailor suit but for me the best part is the backdrop. It is so quietly done it almost disappears but looking closely we see a yacht on the horizon and a dune and grasses just behind the boy. It is an attempt to make the scene as natural as possible. Borkum is a resort island in the Frisians and like most resort photographers, Hans Kretschmann constructed an elaborate effect for what existed naturally just outside his window,

Americans are in the habit of claiming that modern photography began around the end of the First World War, when Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen ditched the soft focus of Pictorialism in favour of sharp, clean lines but there is a lot of evidence to show they weren’t the first; like this 1912 photograph. The woman is using a chair as a prop, as millions had before her, but here instead of merely being a device to add detail to the composition, the back becomes integral to the design, corresponding to the pleats in her skirt. Karl Lützel, the photographer, was fairly prolific in Munich but he wasn’t renowned for his experimentation. A commercial portraitist, he used ideas that were already in place. German, or to be absolutely pedantic, Central European photography, was already developing its own aesthetics when the Americans made their move.

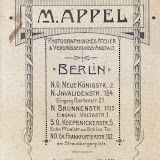

Sometimes the most interesting part of a German carte is its back. Information on Hartmann is scant but it is obvious that by 1902 he had embraced the Jugendstil aesthetic, employing its typography and decorative elements. Well, he was hardly alone in that; just about every photographic studio in Germany was doing it too.

Here’s another example, by the better known Heinrich Axtmann of Plauen. Like most studios he has dispensed with the traditional and difficult to read Gothic font in favour of several others that are simple and clear. This is the modern world after all and in typography as much as architecture, the ridiculously elaborate pretensions of the Baroque and Neo-Classicism have no place in it. Jugendstil was the German version of Art Nouveau but whatever you want to call it, it was a very feminine movement, with tendrils instead of sharp angles and flowers replacing solid shapes.

None of this was necessarily reflected in the photographs themselves although in Axtmann’s portrait here and Hartmann’s above there is more emphasis on the woman’s shape than earlier portraitists would have considered. Notice the way she appears to blend with the background and dissolve at the base; whatever her intentions for having her portrait taken he wanted a study in contours, stripped of extraneous detail. To his eye she could represent the idea of modern sophistication, less an attitude than an appearance.

Germany in the first decade of the 20th century has a somewhat schizophrenic reputation. Berlin was the centre for the most radical ideas and behaviour in Europe and Weimar had been a home for Goethe, Nietzsche and Rudolph Steiner, but away from those places the impression was of a rigid, humourless Protestantism, somewhat like Scotland, and a disciplined militarism. At first glance this couple look to be the epitome of dour, Germanic severity, but look again and you realize she gives off that aura, he’s a little more ambiguous. Something about him suggests a familiarity with the less sophisticated side of Kolberg, which then was in Germany and now is in Poland. If this was taken, as I guess, around 1910, he would have been too young to take part in the Franco-Prussian War and would have had only vague memories of Germany before the declaration of empire in 1871. Compared to what his parents and his offspring experienced, his life was relatively free from turmoil, Germany was rich, he looks prosperous and, judging from her expression, the wife was probably happy to stay at home with her Bible and her knitting while he trawled the streets.

At the turn of the century Germany was producing the best cameras and the sharpest in the world but commercially they failed at photography because unlike the French, the British or the Americans they could not do cute. In other countries photographers had no problem giving a boy in a sailor suit a toy boat and extracting an expression of winsome innocence from him. The Germans tried, like the Wolff studio in Frankfurt did here, but most German children appear to have found it repugnant to put on airs for adults’ sake. The boy looks bemused, the girl frankly irritated at having to dress like Hansel and Gretel, and why not? They’d obviously feel stupid wearing those clothes out on the street so why should they feel different in a photographer’s studio. The girl will go through life getting her own way. Her brother will make one compromise after another until he longs for the sweet mercy of oblivion.

The portrait of this soldier was taken in Berlin, probably between 1905 and 1914. He isn’t wearing any discernable insignia, which suggests he was at an officer training academy. At any time after 1910 he would have known war was inevitable though he might have assumed it would be located in the Balkans and Germany’s main role was to shore up the collapsing Austro-Hungarian Empire. Even in the first months of the war he could have been forgiven for believing an officer’s first role was to provide a model of dignity and poise to his soldiers. After all, everyone around the Kaiser was confident this was a just an argument that would quickly be resolved.

And what of this polished individual? He looks like officer material too though he is young enough to be a student photographed before a ball. Whatever the case, he’s of an age that made frontline action almost inevitable – almost because if his family had money or influence he could have secured a desk job in Berlin. When you think of what was happening in photography and what would come after, it’s easy to dismiss this German period as commercially ordinary but right at the time these portraits were taken August Sander was running a studio in Cologne and producing work of much the same standard. He was also at the beginning stages of his massive compendium of portraits of the German people. A lot of those early efforts depend on the now accepted formula of clean lines, even tones, muted, angled lighting and a complete absence of artificial sentiment. The difference was that Sander didn’t just rely on whoever came through his door but went out looking for his subjects. It isn’t far fetched to see in these portraits a missing link between the 19th century and modern photography.

|

| GERMAN HUMOUR |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Add comments here