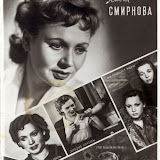

Postcards and portraits from the golden age of Stalinist cinema

"You must remember that for us, cinema is the most important of all the arts,"

Lenin

Back in the 1980s Soviet cinema was still something of a mystery. At one end, the beginning, we had Eisenstein and Vertov, and no matter how excruciatingly boring Battleship Potemkin was to sit through you could accept it was a landmark film. At the other was Tarkovsky, and again, if The Stalker and Solaris were as slow as drying paint they were like nothing else you had seen before. Very little else came out and what did went to the arthouses where they played for a week if they were popular, so between those bookends it was easy to imagine Russian cinema was an entirely strange creature. The few films that emerged from Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary perpetuated the sense. Behind the Iron Curtain they were very good at creating a grey and moody and sometimes a sharp, cold cinematography. You could be forgiven for assuming that all Soviet cinema was like that. If most American films were predictable, all Russian films were art. It was a revelation therefore to find these photo postcards in Bulgaria. Graphically, they are different to anything the Americans were putting out and you can still see something of the 1920s revolutionary posters in them, but they are also a reminder that one possible reason we didn’t see a lot of Russian cinema was that it wasn’t worth showing. Back in the Stalinist era Mosfilm was producing dross that looked like nothing else so much as Hollywood at its banal, self censoring worst.

Musicals were the bread and circuses of Soviet cinema, which comes as no surprise. It is the most soporific of film genres. What’s the point to a musical if not to lull the masses into vicarious high spirits? And what more practical way is there to reinforce a political ideology than to get the audience singing along to it in the aisles? The Soviets were somewhat lagging - the high point of Hollywood musicals had passed by the 1940s – but they had studied the formula. Every musical needed one unforgettable song that people would start humming to as soon as they heard the opening bars. They also needed lavish sets. In Hollywood musicals set design and choreography were more important than the script. Not having seen a Soviet musical it is hard to compare them but Russia being one of the centres of modernist design we can hope there were people who knew exactly what to do with light and shadow, symmetry and movement. Musicals also needed stars. Hollywood and Gene Kelly and Ginger Rogers, Moscow had Lyubov Orlova. Most of her films were directed by her husband, Grigori Aleksandrov. The most popular was Volga Volga (1938), which was reputedly Stalin’s favourite film and concerned a group of singers and musicians travelling up the river to attend a talent contest. At about the same time, Stalin organized a folk festival for the blind Ukrainian folk musicians, the Lirniki. Every known musician attended – several hundred of them - and all were executed. The synopsis to another of Orlova’s musicals, Circus (1935) reads: an American circus artist has a black baby. The only way she can find happiness is among Russian people. Well she would, wouldn’t she?

We in the West tend to assume the only reason Russians joined the Communist Party was as a means to survive. Alla Larionova willingly joined the Komsomol and ran home to show her family her new red tie. It would be years before she understood why her grandmother said nothing but turned and left the room. This photo is a publicity still for the Russian film version of Twelfth Night, where she played Olivia. There is a yet to be written analysis on why foreign tyrants love Shakespeare. It has something to do with his unimpeachable status as a classic but also because he was so politically ambiguous that you can simultaneously show off your cultural credentials while eluding serious analysis. It actually suggests you have very little curiosity (A bit like saying your favourite painter is – yawn - da Vinci.) but that is another hallmark of the tyrant. Avoiding the plays that analysed political power – Hamlet, Macbeth – the Stalinist cinema produced a few films based on Shakespeare’s plays. With the advantage of distance, critics regard them with due respect, inevitably complaining that something is lost in translation from Elizabethan English to 20th century Russian. Just after making this film, Larionova offended some high ranking official and soon had the displeasure to read stories about herself relaxing in bathtubs full of champagne. I would like to say it was Great Western but I think Peter Ustinov already used that line.

History was a problem the Bolsheviks claimed to have dealt with yet never could successfully. How could they wipe the slate clean without destroying the heritage – the Kremlin, St Basil’s, Red Square – which provided the fundamental Russian identity? How do you make a film celebrating Russia’s glorious imperial past while keeping to the line that what replaced it was absolutely necessary? Eisenstein tried with Ivan the Terrible and only saw part one of his epic trilogy released in his lifetime. In 1937 the director Vladimir Petrov released part one of his intended epic about Peter the Great, with Alla Konstantinovna Tarasova playing Katerina, the peasant girl who became Peter’s queen and eventually Tsarina Catherine the Great. It wasn’t the sheer scale of the enterprise that would be daunting so much as how to structure imperial history to suit a leader who regarded himself as a prophet of the modern world and a legitimate heir to the tsars. Petrov was adept at keeping within the boundaries but the trilogy would take nearly thirty years to complete and in its entirety run to over six hours.

The great Russian novelists of the 19th century were realists critical of Tsarist policies and sympathetic to the oppressed so their works were acceptable for translation into cinema. One thing the Russian filmmakers had over their American counterparts was that they weren’t frightened by endurance. This was a land of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, where even short stories unfolded slowly and hung on a small detail like a raised eyebrow. The problem King Vidor had in the 1950s was how pare War and Peace down to 200 minutes. In 1968 Sergei Bondarchuk, husband of Irina Skobtseva (above), released his eight hour (484 mins) interpretation, which for that curious strain of purists who actually care about Tolstoy on screen is the definitive version. Vidor was an avowed anti-communist. If Bondarchuk was he had to keep that to himself but the real difference was that Vidor was under no pressure to show respect to Tolstoy. He could hack out the dull parts of the novel and reduce it to battle and romance scenes if he wanted. Bondarchuk on the other hand was dealing with a sacred text. He had to be faithful to the novel and to Tolstoy’s reputation. War and Peace isn’t famous for being a funny book though there are lots of jokes about it. On Hancock’s Half Hour Tony Hancock once asked a librarian for a copy just so he could stand on it to get another book off the shelf. In The Champions TV series Alexandra Bastedo’s character disposed of it in under a minute. The novel’s status as a classic owes something to so few people actually reading it, though who would need to with an eight hour film version available?

Marina Ladynina was the ideal of Stalinist beauty, meaning she was a standard that Stalin measured all others by. In this portrait she is young and elegant but not too glamorous or fashionable and the things she wants in life aren’t so far above her station. She is in the role of a demure and obedient secretary or some other office worker and while she dresses smartly she is obviously not wearing major fashion labels such as her American equivalent would be obliged to. In the first years of the Revolution artists were expected to experiment and to spread their ideas among the people so photographers like Rodchenko were free to use any means at their disposal to get the message across. Stalin suffocated all that, insisting on stolid social realism. This image is a result. There is something insentient about her that suggests the passive observer. She may have some idea of what is going on but she has learned to look away. Actually, she was one of the leading comedians of the era, renowned for playing the wise cracking, straight talking worker. This image has been heavily airbrushed; there are plenty of others where she shows why she was regarded as one of the most dynamic actresses of her time.

Soviet film directors working in the immediate post-Stalin era often made the point that though the state relaxed his strictures a little the fear remained. Their work in the 1950s was more timid than it could have been (Ditto for Hollywood post McCarthy; the 1950s were that great.) It would be another decade before they gave the envelope a proper nudge. Though Yulian Panich is still alive, there isn’t a huge amount of information available on him. He looks like he spent a good part of the 1950s and early 1960s playing intense and troubled youths, somewhere between Montgomery Clift and any inarticulate British actor in a kitchen sink drama, with a difference. In America the new teen market meant films about hot rods and rock and roll. One of Panich’s roles here, on the far right, was for a 1956 film with the uninspiring title, The Pedagogical Poem, based on a story by Anton Makarenko about how he came to develop his teaching philosophy. Panich must have played the kid who tested Makarenko’s patience until gentle persuasion coaxed him to see the error of his ways. In the still on the left, for the film that translated as Dearest (1957), he looks like any surly and self absorbed American boy whose parents didn’t understand the world was different now.

No doubt there are Russians alive who look back on this era with fondness and nostalgia, not because the films were artistic triumphs but because they represent simple virtues, which is pretty much what people think of American films from the same time. With some notable and rare exceptions, both sides of the Iron Curtain insisted that good always overcame evil, the family was the bedrock of the nation and questioning those two premises would only make your life more complicated and stressful.

|

| SOVIET CINEMA |

Thank you for such a warm-hearted post about Soviet films.

ReplyDelete