Postcards from Nevada – 1940s to ‘50s

“Thanks to the Interstate Highway System, it is now possible to travel across the country from coast to coast without seeing anything.”

Charles Kuralt.

"Devolite Peerless” in the stamp box dates the photographs to the 1950s and ‘Wendover Will’ as the neon cowboy is officially known was erected in 1952. The photographs therefore were taken about the same time Robert Frank was undertaking his epic journey, about midway between that point at the beginning, when the structures Evans found were relatively new and the late ‘70s, when Stephen Shore and others were documenting their decay. Not far from where these photos were taken the US was conducting atomic tests and the territory would henceforth be cloaked in mystery and conspiracy. It was a part of the country people travelled through without really stopping except to fill up the tank or if they were really pushed pull into a small motel for the night. Unlike the Grand Canyon or Monument Valley, this wasn’t a stretch where people were encouraged to stop and ponder. That would be left to photographers.

It is striking how easily, maybe the word is immediately, these photographs fit in with that tradition of documentary photography that began with people like Evans and still survives. An unwritten rule for all these photographers was that the west was not a wilderness but a place of human occupation. Our presence was to be explicit in every frame. This photographer (In the interests of fairness, hereon sometimes referred to as ‘he’, sometimes as ‘she’.) abided by that basic rule. That didn’t have to be. In the 1950s the Nevada Utah stretch of Route 40 was still desolate, with plenty of opportunities to photograph the landscape of cacti and desert scrub pretty much as it had been for millennia. The suspicion is that, like most people travelling through, our photographer found the desert to be quite monotonous. What impressed her was the idea of space and emptiness, meaning the distance between people. A photograph of a barren landscape doesn’t capture that but put some human evidence in the picture and you get it at once. The road with the car in “Great Salt Lake West on US 40 -80” tells you more about the remoteness than the photo would if it were just the bleached landscape and sky.

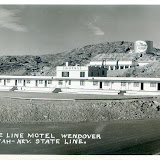

That is part of the reason why gas stations and neon signs became as emblematic of the American west as tumbleweed or saguaro. They are reference points to help us appreciate how isolated we are out there. Think of the number of films or books where someone crossing the desert sees a roadhouse in the distance and (usually mistakenly) imagines it is a place of refuge. In fiction anyway roadhouses are always places where a character’s life takes a sudden turn, usually for the worst. These are places where a man or woman is alone and vulnerable, and the locals are an odd lot. Border towns also have their unique American mythology, partly because of the country’s long tradition of states rights. Nothing much physically changes between Utah and Nevada but on one side we have Mormon territory with its theoretically drug free and puritan ethos and on the other casino land where people are encouraged to indulge their every vice. In American culture the border town is an ambiguous place, where the law is easily thwarted and freedom is always just a few steps away.

At least two photographers from the documentary tradition, Evans and Shore, admitted to a strong influence from commercial postcards. They liked the simplicity of the approach, knowing that a minimum of information was enough to say exactly what needed to be said. Some of these photos stand up against the best of their work in the sense that they get the same atmosphere of strangeness and desolation they aspired to. A Google search uncovered a few more photographs from the same area with similar inscriptions. One was dated 1947, another 1954. The photographer was unidentified. Presumably he worked out of a studio in one of the small towns on the highway, Lovelock, Winnemucca or Wendover, and used the postcards as a way to boost business. I suspect that if the name behind ‘State Line Service’ or ‘Nevada Desert Road’ were known they would have been thoroughly dissected for their meaning and significance by now.

|

| NEVADA GAS |

Wonderful pictures. Thanks John. So evocative. Each frame straight from a B-movie.

ReplyDeleteI know the film Roland. It doesn't end well for him ...

ReplyDelete