“There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.”

Richard Avedon

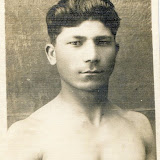

The GAR badge on his cap stands for Grand Army of the Republic, an ex-serviceman’s league for Union veterans of the Civil War. He wears a star on his waistcoat that may be a GAR medal and a small shield above that suggests some official position. These details are useful but it’s the face that draws you in. It’s ragged and dishevelled, ’lived in’ is the common descriptor, and it’s a face you earn rather than buy. Even without the badges to give you clues you know he has seen things no proper mother would want her son to. Some time in the late 1870s or the 1880s this unnamed individual sat for an unknown photographer. There were reasons why the photograph was taken. It doesn’t feel like he was after a portrait for his own interest. He doesn’t look exactly enthusiastic about the situation. It may have been a requirement for his job. It’s also possible the photographer had been commissioned to photograph veterans. Whatever the case, you have to agree that it’s an uncommon study of a man. This is why photography was invented; because painting could never reveal the facts with such immediacy.

When the Academie des Sciences announced that Louis Daguerre had invented a workable, permanent photographic process in 1839 he had to confess that he hadn’t yet been able to take a portrait of a person. It wasn’t so much an admission of failure – no one was claiming the daguerreotype was perfect – but it was an acknowledgement that until somebody captured the human face photography was still a medium in utero. Within a couple of years thousands of portraits of people around the world had been taken and the numbers would rise exponentially (Is there anyone alive who hasn’t been photographed?) but great portraiture has always been elusive. The definitions are too flexible; any photograph that includes a person can be regarded as a portrait and portraiture encompasses a lot of uses of photography, from passport shots to family snaps to elaborately lit and studied studio images, the famous to the anonymous.

When it comes to portraits of unknown people there are a few simple rules that define a great photograph. One is that it should reveal something neither photographer nor subject intended. It can be assumed that the photographer and the veteran weren’t planning on an image that would reveal the harrowing effects of life though that’s what they gave us. A second is that the portrait ought to have some perplexing element to it. The woman in the Sebah & Joaillier portrait above is probably Greek or Armenian. We can say that much, but it is difficult to say how old she is and more than that, we can’t really read what she is thinking from the intensity of her gaze. All great portraits should bother us. A third rule – and maybe it isn’t so much a rule as an ideal - is that the image should be metaphorical, in the sense that it represents a condition, the more subtle and open to interpretation the better. The adjectives we want to use to describe the subjects don’t spring to mind immediately. If they do they are not quite adequate. A great portrait in other words should make us think about things not connected to the image.

All the great portrait photographers made their names photographing the famous but people for whom posing in front of a camera is one of their professional duties quickly learn to adopt a mask. Often we are told that a great portrait of a famous person reveals some hidden, vulnerable side but what we are actually looking at is a game between photographer and subject. That is one reason why celebrity portraiture is ultimately disappointing. What we really want isn’t subterfuge but mystery. Only unknown people can give us that.

VIEW THE GALLERY HERE

|

| PORTRAITS |

Good points. The portrait of the veteran is astonishing, as is the one in the gallery of the Turkish mother and daughter - the mother so drawn and thin; the daughter so plump and confident.

ReplyDeleteAnd I think that looking at portraits of unknown people reveals more about the viewer than the subject. We bring our stories and assume that others will see the same.

ReplyDeleteThe Civil War fellow is so wary, so sad, so impatient.

As usual, wonderful images.