Panoramic

postcards of Egypt by Lehnert & Landrock

“Give

me my robe, put on my crown; I have immortal longings in me.”

Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra

When Rudolph Lehnert and Ernest Landrock

moved their photographic studio from Tunis to Cairo in 1924 they were

announcing to anyone listening that Egypt’s capital was also the cultural

capital of the Middle East. Not that they decided this: the year before, Howard

Carter and his team had broken into Tutankhamen’s tomb and Ancient Egypt had

once again become the most exciting idea on the planet. In far off Hastings,

builders excavating a basement discovered some odd glyphs in a dingy tunnel and

for a moment the theory that ancient Egyptians or Phoenicians had visited the

place was kicked around. The place called Ancient Egypt, or at least the idea

of it, had seldom been out of fashion’s eye in the last fifty years but now it

was back centre stage. There were at least half a dozen other companies in

Cairo producing real photo postcards for the European market but Lehnert &

Landrock would become the best known.

Lehnert, the photographer, had certainly

worked in Egypt before the company opened shop there but once it did, business

flourished. We can think of its halcyon years as coming between 1924 and the

beginning of the war. Although a great enthusiasm among the British for German

product seems unpatriotic, even love of country has its limits. There was a

booming international market for shots of L&L’s most renowned genre: nude

Bedouin women, and the British were driving demand as much as anyone else. But

anyway, we’re not here to talk about that, or even more dubious genres the

company marketed but rather the flip side; Egypt as a phenomenon of cultural

sophistication.

From the beginning, postcards were the

familiar size by which we know them, approximately 3½ x 6 inches, because they

fitted the standard envelopes for informal correspondence. In some countries

the laws sounded specific; the post card had to be ‘no more than’ or ‘less

than’ or ‘at least’, but this only meant that anything that fitted within the

required dimensions was legitimate. Publishers produced midget size and giant

size postcards but the most common irregular format was the bookmark size, and

though bookmarks of stage stars were popular, landscapes and street views have

become the most enduring, especially the bookmark postcards from Cairo that

Lehnert and Landrock produced.

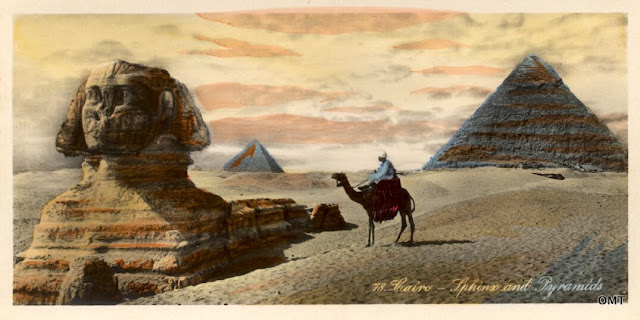

One of the company’s achievements was that

it managed to make Egypt look how everyone imagined it to be; a land still

touched by its ancient past, with oases of palm trees providing shade from

which to contemplate the pyramids, maze-like souks, the stalls piled high with

ornate rugs and silverware, and watched over by hawk-eyed Muslims. One hundred

years ago, the abiding image of Muslims was of devout, silent and impassive

people. Of course, not long before in the Sudan and southern parts of Egypt

Muslims were fanatics who needed to be suppressed with violence if necessary,

but that was now the past. In popular culture the siege of Khartoum was just

another heroic chapter in the history of the British Empire.

From 1882 until 1922 Egypt was officially a

British protectorate (and less officially into the 1950s). This explains why

Cairo, a city inhabited by Egyptians since 969 CE would have a ‘native quarter’. This was both a ghetto and a slum –

neither being necessarily the same thing – separate from areas occupied by

Europeans, Armenians, Alexandrine Greeks, Jews and Ottoman Turks. Egypt at this

time, well, until 1914, was also a khedivate of the Ottoman Empire. The

condition for Egyptians was something like being the child of two parents whose

contempt for each other was outmatched by that for their offspring. Said

children are usually destined for a miserable adulthood.

Cleopatra, Khartoum, The Greatest Story Ever Told: in the

1960s Egypt became the canvas for epic visions, though ‘bombastic’ might be a

better adjective. There’s a suspicion, and maybe nothing more, that one

influence was these panoramic views; well they share the same format and there

is something about the panorama, no matter how small, that speaks of the vast –

in time as well as space. To create this image the studio simply took a

standard format negative and cropped what wasn’t needed. There isn’t the

distortion a genuine panoramic camera would produce. Still, removing whatever

was extraneous and leaving the palms, the camel, the cart and the porter

suggests a scene that could take place anytime in the last 200 years.

Interestingly this is titled Kasr el Nil

Bridge but it may be the one it replaced in 1931, the Kobri el Gezira. Photos of that one have the palms but they are

absent in views of the later bridge.

The Orientalist argument says that these

views tell us more about the consumers than the place, which should be beyond

dispute by now, but what after all do they tell us about Cairo? Where, for one

thing, are the crowds? Today the city is so densely packed that a view like

this one seems impossible even at unlikely hours. Was it really so magically

empty in the 1920s? No. As far back at the 1500s, when Europeans began arguing

over the biggest, the richest and the most powerful cities in the world, three

were inevitably ignored: Peking, Bombay and Cairo. As engines of civilization

they were derided, despite the monumental evidence opposing that, and despite

the popularity of Ancient Egypt stemming from the great desire of London,

Paris, Rome etc to be seen as the inevitable heir to its culture. So no; this

is not the vast, hectic and noisy city tourists encountered but somewhere ancient

and austere: the place they came to find.

| ANCIENT HISTORY |