“A person can stand almost anything except a succession of ordinary days.”

Goethe

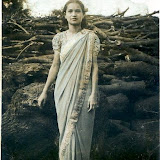

As photographs they aren’t particularly interesting, being typical of millions of cabinet cards produced in the US in the 1880s, but precisely because of that we can use them as a starting point to consider what it meant to be a small town photographer in America in the late 19th century. At a time when there was a debate in the cities as to whether or not photography was an art, people like Clarence Hunt regarded themselves as tradesmen. Success depended entirely upon the number of customers and in a town like Franklin Falls, which today we’d think of as a village, there wasn’t much chance of getting rich or famous. Once a town reached a certain size a studio photographer became essential but it was an occupation for people of middling ambitions.

C. L Hunt was born in 1852. By 1881 he was operating as a watchmaker and jeweller on Central Ave, Franklin Falls, and by 1888 he had branched into photography. The move wasn’t unusual. It was common for photographers to run two or three businesses out of the same shopfront and jewellery and photography had certain affinities. Both involved a working knowledge of chemistry, the use of mechanical instruments and detailed work. A jeweller working with electroplating and engraving should have easily adapted to photography. Economically it made sense. Neither occupation could have been sustained on its own and being a merchant by disposition he would have understood the logic in diversifying. The elaborate studio backdrop in the group portrait indicates he had at least a moderate sized studio. He would have had a staff as well; a receptionist and at least one assistant in the studio and/or the darkroom.

Franklin Falls was a mill town just outside Franklin on the Merrimack River in New Hampshire. Maps and photographs from the 1880s suggest there were probably no more than 3000 people living in Franklin, a population large enough to sustain one photographer, two at the most. Other photographs by Hunt online show he took a few landscapes and did some advertising work but mostly he was a portraitist who followed orthodox procedures. Prices for photographs varied between towns and states and by the 1880s they had fallen considerably over the previous 25 years but a working figure would be between 25 and 50 cents per cabinet card. Cost of living figures for nearby Connecticut show that in 1880 the average wage there was $1.75 per day. At a very rough guess, Hunt would have needed 5 or 6 customers a day just to stay afloat. Presumably he got them because he was still registered as a photographer at Central St in 1895 and worked at least another 7 years.

Go to a newspaper archive from New York or Chicago in the 1880s and search for ‘photographer’ and ‘suicide’. There are a few entries and they tell much the same story. A photographer doing alright for himself in a small town decided to try his luck in the big city. Things didn’t work out and one night he returned to his room in a shabby boarding house and put an end to his suffering. Photography was a cutthroat business, particularly at a time when the technology was rapidly evolving. The shift from albumen to gelatine based prints for example required a whole new investment in equipment at the same time as the new processes were making the production of photographs much cheaper. One way to survive was not to innovate. Keeping to a formula his customers were familiar with, he could turn out a steady number of portraits and the only adaptations required were in small technological advances. Electric lighting for example was around in the 1890s although he might not have used it because it was expensive and the studio skylights worked just as well. By the turn of the century albumen printing was redundant but still available. The cabinet card was also on the way out. If Hunt, now in his fifties, thought he was too old or close to retirement to change he would have watched the arrival of the Kodak camera with a somewhat indifferent resignation, realizing that in a few short years his most important clients were likely to be the mills and local businesses needing advertising. The real legacy of people like Hunt is that we have an archive of images of ordinary citizens from small towns, people who, like Hunt, had no ambitions to immortality but have been bestowed with something resembling it.

VIEW THE GALLERY HERE

|

| C L HUNT |