Postcards

of bad weather

“There is really no such thing as bad weather, only

different kinds of good weather.”

John

Ruskin

Canadians

talk about the weather a lot, which in some peoples’ minds mark them as a dull

breed, but when the temperature can drop fifteen degrees overnight and bring a

metre and a half of snow with it you think they are entitled. Most of us don’t

live in places with really bad weather (yet). Civilization has tended to settle

the temperate areas. Even in the tropics with their seasonal cyclones and

hurricanes, if you read about a high death toll the real story is about shoddy

infrastructure and government neglect. That was what happened in Somerset

earlier this year. Had government departments listened to professional advice

given earlier, the flood damage could have been lessened. After all, it wasn’t

as though the floods were a complete surprise. For centuries Somerset and the

south coast of Britain has been subject to floods. The big difference is that a

really bad one would occur only two or three times a century, time enough to

recover, but just the year before serious flooding had affected Yorkshire and

parts of the Midlands and meteorologists were knowledgeable enough about the

behaviour of the jet streams to predict them. Climate change means the Somerset

floods could become annual events. All it takes is an aberration in the

atmosphere above the tropics in August for torrential rain to hit Britain in

December, and postcards like the one above will lose their interest as they

presage massive losses ahead.

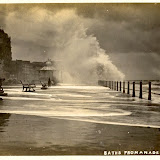

The

storms that used to hit the south coast of Britain every year were spectacular

but less threatening than they appeared, being driven by high winds and

thunderstorms rather than heavy rain. The photographer is not credited on this

or the postcard above but though two likely culprits are Fred Judge and Henry

Godbold it turns out that photographing the annual storms was a popular event.

It was a test of the photographers’ skill in capturing the moment the wave crashed

upon the promenade, and nerves because they had to get close enough to risk

having their equipment, not to mention themselves, washed away.

Here’s

one we know is by Judge that gets the timing perfect but he must have been so

close that it soaked him. Was it worth the trouble? Being a commercial

photographer, he would have calculated that in monetary terms but when we look

around and see the competition we realize how high the stakes were. Each

postcard sold for a penny and if a good one sold 1000 copies (not unreasonable;

popular postcards could sell in the tens of thousands) we start to see how a

drenching could be a small price for a big return.

Here’s

another, and a personal favourite from the Judge collection seeing as it is so dramatic. This being around 1910, probably just before, he would have used a

tripod and possibly plate film, which meant he only had one chance at this

particular scene. Of course another wave would come along in a few minutes but

he would have missed the composition with the spectators. Notice, incidentally,

how close everyone is to the breaking wave. It seems it wasn’t as dangerous as

it looked, or else the good people of Hastings lacked something in the department of common

sense.

To

Cologne, and the great flood of 1930. Being on the Rhine floodplain, the city

has always been subject to flooding, but the events of November 1930 were

beyond what anyone expected. Beginning with windstorms (sometimes incorrectly

called hurricanes) the centre of the city was soon submerged as torrential rain moved in. This is a reminder that there were really only two reasons to take postcards of wild weather. One was that they made for spectacular images and the other was that they were news events.

But

Cologne was not the only place to suffer. The floods of November 1930 affected

all of Europe, across to the Scottish highlands. The list of damages reported

in the press was staggering: seven dead in France, at least thirty in Germany,

dykes bursting in Belgium and Holland, Russia cut off, ships run aground, all

of Holland under water, power stations destroyed, the Spanish and Portuguese

coasts awash. It would however be by no means the worst storm to hit Europe in

the twentieth century, and as stories of European disasters in the 1930s it would soon be overshadowed.

And

oddly, it appears that is Cologne was where most of the postcards came from. There must be some from other countries but they are scarce.

Even more oddly, most of the Cologne shots suggest peaceful vistas rather than scenes of

destruction. In the end it depends on how you look at them. We have become so

used to images of nature at its most violent that we easily overlook the

possibility that in 1930 scenes like these from Cologne could have been read as

documents of terrible destruction. What mattered wasn’t so much the intrinsic

drama of the image but the sheer expanse of the flooding. Like the images of

the Somerset floods earlier this year, the most remarkable weren’t of families

in despair – we see that kind of thing every day from the press – but the

aerial shots that showed whole villages under water. It seems however that

before long we will become inured to those as well.

|

| STORMY WEATHER |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Add comments here