Studio

portraits from around the world

“If you

understood everything I said, you’d be me.”

Miles Davis

Reading American histories of photography can give the

impression that not much happened beyond the borders of the US. In particular

there is a persistent line that vernacular photography is somehow indigenous to

the U.S. Luc Sante says as much in Folk

Photography, it is an underlying argument in The Art of the American Snapshot and these are good books by

respectable scholars. If you accept the argument that it is indigenous then

everything is framed within an American consciousness (whatever that is) but if

you say it isn’t, it is global, things become much more interesting. Why, for

one, did everyone behave the same way in front of and behind the camera? And

despite all the work scholars put into identifying national characters

(especially in countries like Australia where the notion is extremely fluid or

possibly never existed) do photographic portraits expose the futility of the project?

The above portrait comes from Cuba, but you wouldn’t know that unless you read

the inscription on the back. It was bought in Turkey. The family could easily

be Turkish.

Here’s one from China. Obviously the man is Asian and

there’s a banner with Chinese script around the tree but if you consider just

his posture and the other details in the backdrop, you couldn’t say for sure

this wasn’t taken in San Francisco or London or some other western city with a

high Chinese population. The painting might look Oriental though I’m not sure

we would think that if the subject was European and the script on the banner

was Cyrillic. Then you have to ask what difference that would make.

A case in point: The backdrop in this Bulgarian portrait is

just as elaborate and what might first appear to be a mountain in the

background is a village. There’s one in the Chinese postcard as well. Both men

have a poise that suggests they want to appear relaxed but can’t quite get

there. Perhaps the backdrop affects them; it does give an air of artificiality

to the scene that they might have found absurd.

There has been a bit of work in recent years analysing

posture and gaze in studio portraiture. A lot of it is unconvincing. Americans

might assume the real photo postcard is indigenous but they don’t get into the

same difficulties as people trying to find cultural or ethnic distinctions in

portraits. They make the same mistake; excluding examples that sully their

case, but also they are frequently reduced to taking into account other details

such as dress to make their point. Gesture and gaze are too ambivalent. This

one is from Australia. Because of that, I’m inclined to think her muff is made

from kangaroo pelt. It helps identify where she comes from, because nothing else in the

photo does.

Position in photographs is important. In April 2012 the

Turkish newspaper Aydinlik ran two portraits side by side under

the headline “Bize Hangisi Yakışır”, or ‘which suits us best?” One showed

President Kemal Ataturk and Prime Minister Fethi Okyar standing stiffly behind

their wives, who were seated. Next to that was a studio photo of President Gül

and Prime Minister Erdoǧan sitting, tieless and relaxed while their wives stood

behind them. The article was obscure in its intention. The newspaper is associated

with left wing trade unions and critical of the present Government. It is also

worth recalling that Ataturk extended many rights to women, including the vote,

while under the AKP, the status of Turkish women according to international

indexes has noticeably diminished, yet the comparison appeared to suggest that

Gül and Erdoǧan were comfortable giving power to their wives. The suspicion is

that the newspaper tried to take a swing at the Government and missed;

nevertheless the example shows how important position and posture can be in

formal portraits.

According to these codes, the person in the highest

position, the woman in this American portrait, has some dominance over her

husband, but from the looks of things he’d disagree. There’s a sense, and you

get this from his posture, that he knows where the power ultimately rests.

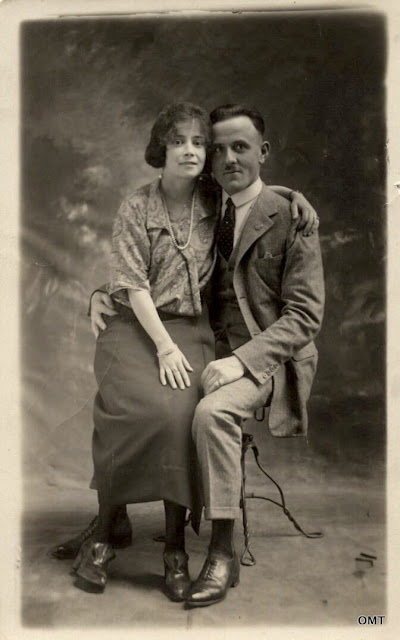

And what about this one from Canada? Does it actually say

something about marital relations in Canada in the 1920s, or is it only about

the marriage between these two? It was bought in Montreal and might have come

from Quebec but in that case bear in mind that while in most Canadian provinces

women got the vote around 1918, in Quebec they didn’t until 1940, well after

Turkey. If we want to take the point of view that position and posture in

photographs reflect social standing across the whole society, this image messes

things up. If we consider it instead as reflecting the situation of two

individuals, we have to wonder how much we can attribute to position and

posture. (You’ll notice, by the way, how most of the men have similar

moustaches despite coming from different countries. What could that mean?)

So, a Romanian boy …

Is not that much different to a Turkish boy …

Whose mother could be French …

Or German …

Or Filipino...

Whatever the case, American claims that there is something indigenous about vernacular photography are false but so are notions we can divine any implicit cultural meaning from gesture, position or posture. If these portraits reveal anything it is not what we are looking for.

Whatever the case, American claims that there is something indigenous about vernacular photography are false but so are notions we can divine any implicit cultural meaning from gesture, position or posture. If these portraits reveal anything it is not what we are looking for.

|

| ANGLO SAXON ATTITUDES |