“If I could do

it, I'd do no writing at all here. It would be photographs; the rest would be

fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces

of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and excrement... a piece of

the body torn out by the roots might be more to the point.”

James Agee

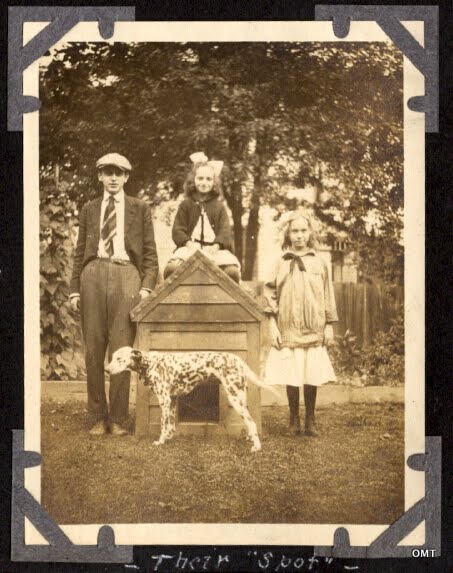

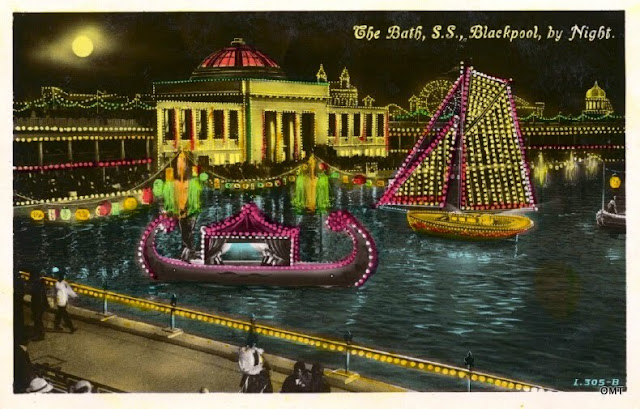

An album found in Ottawa, filled with more than sixty photographs taken in New York State and thereabouts between 1916 and 1920. Most of the images have captions and were carefully placed in pages that were then dated. This tells us it was put together some years after the fact. What that fact was becomes one of the album’s essential mysteries.

The photos

are of the German community living around Utica in Oneida County C WW1. In the

way that Swedish emigrants settled throughout the upper Midwest, Ukrainians the

Canadian prairies and Basque sheepherders made Nevada their own, the great

arrival of German emigrants that began in the 1850s became established

predominantly in mill towns in the north-east. Unlike earlier waves of

immigrants (nice phrase that; sort of like David Cameron’s ‘hordes of refugees’

but obviously better dressed), the Germans of the mid-19th century were

motivated by economics and were not escaping religious persecution. The

Anabaptists – Amish, Mennonite, Hutterite – who had arrived in the seventeenth

century were exclusive and kept to themselves but where Germans settled in the

1850s they formed communities where it was common to see a Lutheran and a

Catholic church close by each other. Several local histories suggest that back

in Bavaria or the Rhineland, Protestants and Catholics kept a deliberate

distance from each other but in towns like Utica the Catholic Germans were more

likely to hang out with their Lutheran compatriots than their Irish brethren.

Around

the same time these photos were taken, over in Hustiford. Wisconsin, German had

become established as the majority language, meaning that a generation after their

parents arrived the children had no need to learn English. Even non-German

residents saw the necessity in learning the German language. The people in

these photos are also most likely first generation, defined as being born in

the U.S though their parents weren’t. The terms ‘first’ and ‘second’ generation

need clarifying since demographers appear to use both interchangeably. Whoever

put the album together used English in the captions so considered him or

herself a native English speaker but probably spoke German at home.

They ate

and drank German too. Prior to the generation from the 1850s becoming

established, beer was not especially popular in the U.S. Within the decade the

new arrivals set to put things right. Soon enough Pabst, Coors and Budweiser were

unleashed upon the world, leaving non-Americans to shudder at the thought

things had somehow improved. That generation of Germans also introduced bacon

and ultimately the hot dog, pretty much guaranteeing that America will be

bed-ridden by 2100CE and effectively deceased soon after.

A quick

skim through the archives doesn’t throw up a Nellie Stiefvater in Utica but a

Nellie Wilson born in California on September 17 1877 and dying in May 20 1959,

did marry a Julius Stiefvater: all events taking place in the same state. We do

find dozens of Stiefvaters in the cemetery records across Oneida County. Like

Tremblay in Montreal, it appears that the surname has become so synonymous with

place that others from different parts of New York might have assumed at once

that a Stietvater came from Utica.

What

about Henry Witte? On draft card Form 886 No.99 we have a Henry Witte, born

January 29 1889 and resident at 526 Varick St, Utica. What are the chances this

is the same? He fits the bill, but the Henry on the card describes himself as a

conscientious objector “opposed to warfare”. This is interesting. Who possessing the merest spark of an IQ isn’t

opposed to war? Thousands of Americans tried to declare themselves

conscientious objectors in WW1, especially after reading what was going on in

France, but there were very few grounds for having the claim accepted without a

trial, which was costly, undignified and guaranteed to end in some form of

imprisonment. One was if you belonged to a handful of recognized religious

groups like the Amish or the Mennonites, and both were originally Germanic.

What if the Henry Witte in the public records argued, not unreasonably, that he

was opposed to going to war against his ancestral homeland?

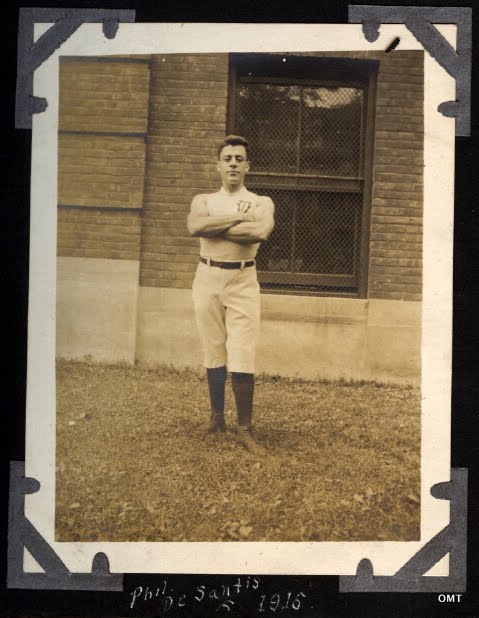

The turnvereins were German community sporting clubs. When they began in Germany during the Napoleonic era they had a marked nationalistic aspect – the idea was to breed a generation of physically healthy German youths who would defend the Fatherland when required (hmm). By the time they were established in the U.S the politics had lost its sting. They were more about getting der jungen from one factory town to play der jungen from another while der mutters und der vaters drank beer, ate sausages and cheered like crazy.

The people in these photos are not just very

normal looking; they are very normal looking Americans. The Henry Witte photo is the only one where the war gets

a mention. That’s not surprising; it’s only a reminder that photo albums tell

the truth but they don’t tell the story.

It must have been hard for a Stiefvater to walk to school in 1916, let

alone 1917 when the U.S entered the war.

But could we be looking for something that

isn’t there? There’s that line that sooner or later every historian feels

obliged to quote: ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. There are

all manner of events and situations we don’t see in these photographs simply

because they are not something that would have invited a photograph. That’s the

problem with photo albums: they don’t show us the highs and lows so often as

the grey spaces in between.

I do not think it is a Model T because if

it was it should have grilles on the bonnet. There are several other candidates

including the Detroiter, the Scripps-Booth Rocket, the Turnbull Runabout and

even the Saxon Roadster, all of which sound like someone’s dream machine, but

the more important question is who Wenzel is; apart from being the one with his

hands on the steering wheel of course. What’s his relationship with the

photographer? Have we met him before? What’s the point of a photo if it offers

evidence then fails to explain what it is evidence of?

We’re lucky. It’s not that albums like this

tell us what we don’t know but what we never thought much about. Prior to

discovering this album, what might be called a history of the German Diaspora

to the U.S was more accurately described as a statistic, so far as I was

concerned anyway, and that’s being generous. It’s history from the side door:

we should appreciate that.

VIEW THE GALLERY HERE

|

| A MINOR PLACE |