"You should have come down and had Christmas dinner with us. We had a chook but it was as hard as a football."

Ruth Park, The Harp in the South

Ruth Park died on December 14th. She was 93. This may not mean much to non-Australians but her two novels set in Surry Hills during the Depression, The Harp in the South (1948) and Poor Man’s Orange (1949) have become Australian classics. Park wouldn’t hear a bad word against her husband, Darcy Niland, yet there are reasons why her novels remain in print when most of his have been forgotten.

Park wrote a lot more children’s books than she did adult fiction. She is a link between authors like Niland and the playwright Ray Lawler, who describe the lives of working class men and women, and children’s writers like Colin Thiele or Ivan Southall and they all have something in common. Long before intellectuals started problematizing the idea of ‘Australian identity’, they were certain of what it wasn’t. English children had drab lives trapped in dirty, polluted cities and they didn’t get up to a great deal. Australian children lived in small country towns. They rode horses, fished in creeks and got involved in all manner of scrapes and hijinks. Even the adults with their various afflictions and woes understood how fortunate they were. The writers weren’t that inept to claim that life was perfect but when you compared Australia to other countries it was about as close as anywhere got. And the worst place a child could end up in was England. Even if Australians sang ‘God Save the King’ whenever it was required of them (every conceivable opportunity) and radio announcers still affected BBC English accents, how could you trade the eternal sunshine of an Australian childhood for grim, damp England?

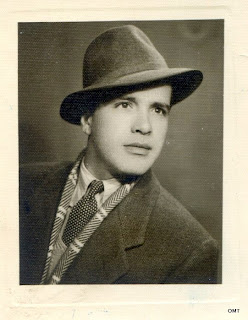

Not too many people remember their childhood in Australia being quite so carefree and adventurous as Park, Thiele et al made out. Still, they can recall moments and, as it happens, a lot of old family photo albums give us glimpses that prove the writers weren’t just spinning fantasies. Obviously, people photograph what they want to remember and they are very selective, but the photos here could all be scenes and portraits from a ‘timeless Australian classic’. All of those children’s writers traded on a nostalgia for their own childhoods – what was or what ought to have been – and even the books they published in the early 1970s had the feel of a time since past. They kept up to date with technology but the sensibility and the values belonged to more distant times.

If that world of long summers in magical small towns ever existed for longer than the press of a camera shutter then you have to say that by the late 1960s it had vanished. Most people now lived in the cities and more of them were going to university. A different consciousness took root. Filmmakers in particular turned on the country towns. They became places where the Aboriginal residents had wretched lives, the town drunks were no longer lovable but mean and beat their wives and inevitably, the smaller the town the more sinister its secrets. Shame, The Cars that Ate Paris and Summerfield represented a loss of innocence that was long overdue though their point of view was every bit as romanticised as what had come before, just darker.

|

| AUSTRALIA |