“A man in love is

incomplete until he is married. Then he is finished.”

Zsa Zsa Gabor

To be an army officer in Turkey in the 1940s and ‘50s gave a

man more status than lawyers or doctors could expect. You might not have made

more money but you were a defender of the nation, so when the time came to get

married full military dress said more about you than any well-tailored suit

could. It might have even been expected, since several of your commanding

officers were obligatory guests and according to protocol you were not supposed

to appear before them in civilian clothes. Having the groom in his military

uniform does tend to add a slightly sinister quality to a wedding photo, but

even if he were wearing standard black tie in this scene it would still suggest

this wasn’t exactly the happiest day in a young couple’s life. Everyone,

including the little boy in the left foreground, seems to regard the camera

with suspicion, even hostility. It also looks like they have crammed into an

office, or a back room at the registry.

But before we start thinking that the Turkish marriage is a

dry, sombre affair, a farewell rather than a greeting, consider this snapshot.

Apart from the fact that, finally, we get a smiling bride, there’s a suggestion

the woman with her has donned a turban and applied some blackface. It’s the

difference in shade between her face and her arm that make us think so, but could

she? Would she? I don’t see why not. Weddings are usually supposed to be fun

and it wouldn’t be the last time someone attempted to brighten proceedings with

a display of bad taste. At least the bride is laughing.

Here we get a scene that suggests some ritual is about to

take place. He appears to be a relative rather than the groom and it is

possible he has decided to offer some prayers for the couple. Everything about

the scene points to hasty improvisation; important details that were overlooked

in the hectic rush of the last few days. He had a speech prepared but he left

it at home, or thinking how quickly his daughter or his niece has grown up

fills him with an existential dread. She wants him to know that everything will

be all right, but actually, she’s used to his sudden spells. This is nothing,

but she wishes her sister would put the camera down for once.

Let’s leave Turkey for a while and head to Canada, to contemplate

for a moment how utterly boring it must be being a professional wedding

photographer, heading out all day every weekend to take the same photos over

and over. Professionals are paid to capture that special day but what they

record is a formula. Only family and friends can photograph the day properly.

Being the 1950s, this might have been taken at the bride’s home; which is to

say her parents’. It’s a moment where past, present and future come together,

for this being Canada in the 1950s she will probably have the same wallpaper in

her new home, which will be a triumph of domestic taste and design. Mum would

have taken the photo; Dad could have but he was in the kitchen knocking back

his third bourbon of the morning, on account of nerves.

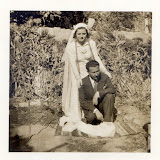

Another Canadian marriage scene; this one taken out in the

rural wilds of Ontario. It makes you wonder why people hire professional

photographers at all. A professional would have resisted photographing the

couple with the farm as a background, preferring a studio setting with a

neutral background, but the whole point of wedding photography is to preserve

memories of the day. The only memory a commercial photograph would record is

that of the experience of being photographed. Here we get an actual incident.

The couple are already married and about to drive off for their honeymoon. They

don’t look like a couple of farmers, but then women in wedding dresses seldom

do. We can speculate on why they are out on the farm but we can’t deny this is

a moment that will stay with them.

To England, and a photo that looks like someone’s attempt to

create the studio look, with the blanket draped over as a backdrop. Everything

about the scene is slightly ratty, from the man’s ill-fitting suit to the cheap

blanket and the dingy doorway. They probably couldn’t afford a professional

photographer, but they didn’t need one. We do hope he’s not a proper Jack the Lad, with a spare bird out in Chelmsford and a couple of geezers on his back for some readies he

promised to cough up last week; that would break her heart.

Another Turkish snapshot, that also looks like it was taken

at the registry office. Notice how the bride and the woman to her right have

their eyes shut against the flash. The boy next to the bride has covered his

eyes. But then the woman next to him and the one above her have expressions of

stark terror. The man just behind the bride has an inane grin. Others are

trying to push into the photo or preserve their dignity. The man at the far

left looks like he has just realized he left the stove on at home. Think of

those millions of photos of everyone standing to attention on the church steps.

This one is what a wedding photo should look like.

Apart from making marriage a civil ceremony, the Ataturk

government tried to outlaw polygamy and arranged and consanguineous marriages,

but these were rooted in long traditions and out in the hinterland people stuck

to them. This photo was taken in the 1920s, not long after the birth of the

Republic and it presents the image of contemporary Turkish society, or what it

should have been: an urbane couple without a hint of religious symbolism in

sight. The woman’s headdress suggests she is Armenian, so here we encounter one

of the conundrums at the heart of Ataturk’s revolution. With outwardly western

values, better connections with Europe, a higher level of education and, in

urban centres, more prosperity, on the surface the Armenian community embodied

the new ideal, but how could that be so much as suggested after 1915? Compare

it to the top photo and we see how it is one thing to adopt the manners, quite

another to accept the mores.

|

| LOVE AND MARRIAGE |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Add comments here