“I have vision and the rest of the world has bifocals.”

Paul

Newman as Butch Cassidy in Butch Cassidy

and the Sundance Kid (1969)

Ansel

Adams’ photographs are boring. Those heavily burned in dark clouds above

mountains in sharp focus tell us as much about the landscape of the American

west as a John Wayne film shot on a backlot. I once listened to a talk by

someone who argued that Adams was a Pictorialist who discovered the focus ring

on his camera. I couldn’t disagree. For all the claims about him being at the

forefront of American modernism, he clung to the Pictorialist values of image

over content and the print as a surface for manufacturing illusion long after

they had outlived their usefulness, except as a faintly nationalistic idea of

the west as repository for America’s soul. The real modernists, the people who

thought there was a much more elemental way of depicting the landscape, mostly

escaped the attention of the museums, the critics and the academies until it

was too late.

One

of them was Burton Frasher (1888 to 1950) who, between about 1920 and 1950

travelled across the southwest, from California, through Nevada, Arizona, Utah

and New Mexico, leaving as his legacy thousands of photographs of the

landscape. You wouldn’t exactly describe him as unsung: there is a huge online

archive of his work available through the Pomona Library and it has a couple of

accompanying articles, including an interview with his son, Burton Jnr, that

may be the most comprehensive description of a postcard photographer at work.

Some of us think the idea of driving across the landscape and taking

photographs is the ideal job, but one thing that comes across in the interview

is how hard photographers like Frasher worked. The market was cutthroat, they

could not afford to slacken their output and they were constantly on the road.

When Frasher started out, ‘the road’ was often dirt tracks and the cars weren’t

well designed for them. When the Lincoln Highway travel guide was first

published in 1915, it advised drivers to carry almost a whole engine’s worth of

replacement parts because once the highway entered Utah anything could happen.

By the 1920s it could recommend newly built gas stations and roadhouses along

the way but spare tyres, fan belts, spark plugs and chains were still

essential. This then is Frasher’s world. It can’t have been that rough. Where

else were you going to get views like this one?

One

reason that Frasher may not have got the attention he deserves was that he was

primarily a commercial photographer, and that meant that there were a lot of

clichés among the wonderful views: cacti at sunset, cute animals and scenes

like this. The rider on the rise gazing across the desert had already been done

to death by the time Frasher took this, and that may have been why he chose to.

He could be sure it would sell. This is the west of Marlboro ads. It’s the type

of image where every element in itself is depicted perfectly but in combination

they add to very little.

Frasher’s

real value to us lies in scenes where he is taking part in the creation of a

myth rather than recreating old ones. Back when he took this the desert highway

gas station wasn’t yet a cultural icon. Greyhound had pushed a campaign in the

1930s encouraging Americans to take their new streamlined buses cross-country

and the scene of someone arriving in a small town by bus was common enough in

films but images like this would really belong to the post-war boom. These days

we’ve seen so many road movies that we recognize it at once, and there’s no

shortage of photos of abandoned and decaying gas stations. This belongs to an

era when Chevron was a relative newcomer to Arizona. Note the oil stain leading

in.

What

does Frasher mean by “today, along North Virginia St”? Presumably he is

measuring North Virginia St of the 1930s against the past, in which case he is

asking us to see how it has changed, or hasn’t, since the days of the Comstock

Lode silver rush. . The Western Nevada Historic Photo Collection has an image

of the Pioneer Drug Store (the shop the man is standing outside of) that could

have been taken on the same day and even by Frasher, though it is unaccredited .

The building was constructed during the mining era, the actual drugstore may

have been. Though the town now has electricity, telephones and cars, Frasher

seems to be suggesting that very little has changed in essence. The two really

interesting details are the advertisement for postcards on the pole to the

man’s left, and the advertisement for Kodak developing films on the window to

his right. My guess is that Frasher did business with the owners and that may

be one there. I do not understand why our great grandfathers thought a three

piece suit was the proper thing to wear in the desert.

I

had a post some months back about Frasher’s photos of Native Americans. If his

studies of Navajo, Apache, Hopi and Acoma people are not his best work, they

constitute the most interesting reading. He swings between frank depictions and

the frankly banal, being aware of the poverty and wretched conditions in one

scene then playing up the most gratuitous stereotypes in others. This was taken

at the Little Colorado Trading Post, now called the Cameron Trading Post.

What’s interesting here are the dynamics between the group and those with the

photographer. We see hostility, or at the least apprehension, indifference and

some willingness. Though the scene is arranged, this was not a world where a

white man could turn up with a camera and order people about. Nor were the

Navajos likely to do as they were told just because Frasher was a familiar

figure. The feeling is that he had some rapport with them, to the extent he

probably spoke Navajo, but just because someone was willing to sit for him,

that didn’t mean they had to behave as he wanted. There are lots of details to

consider in this scene, from the physical structure with the people descending

to the background to the detritus, the saddles, pots and bowls lying about.

There may have been some arrangement of the people but nothing else in the

scene has been touched. That isn’t a small point. In the 1930s and well beyond,

National Geographic photographers

commonly fitted up scenes to show things the way they thought they should be. In

this case, others may have seen the stuff lying about as proof of the Navajos’

social irresponsibility but to Frasher this is the way things are. People leave

bowls over the doorway because they do.

The

personal Frasher collection is regrettably small. If I had more to show, I

would. Some of his best photographs are of industrial scenes in the new west of

the 1930s. If you thought Ansel Adams was the eminent modernist of the era,

that’s because you haven’t seen Frasher’s views of Boulder Dam or the

Californian oil wells. But he was also a good historian. I won’t say ‘great’,

because his idea of history is largely directed by the tourist industry. Take

the Calico graveyard. In the 1930s, as tourists began crossing the west, old

ghost towns like Calico that had been considered little more than rubble a few

years earlier suddenly became popular sites. And if you wanted a vivid

experience of the old west, what better than a graveyard out in the desert,

lined with memorials to prospectors, cowboys and outlaws who had met their

maker prematurely? Forget Adams and think for a moment of Walker Evan’s famous

image of a grave in (I think) Alabama. It is anonymous; barely a ripple in the

gravel, but what has excited many critics is the originality of Evans’s idea: a grave!

How surprisingly familiar. Who else would have thought of it? Well, a critic might be someone between proper jobs

but anyway, I prefer Frasher to Evans on this one. Because there are several

graves there is a more macabre atmosphere, but simultaneously, and more

importantly, an awareness that these piles of stones belong to people;

something more real. There’s also a

sense here of eternity in the peace of the desert. Fully convinced that once I

die that’s it, no trumpets welcoming me to the pearly gates, I’d prefer to be

placed out here than just about anywhere else I can think of.

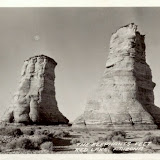

If

I haven’t any Frasher views of industry here to convince you he deserves more

attention that is only because I have always preferred his other scenes,

particularly of the Arizona desert. I don’t think it is overheated hype to say

that Frasher found his eye in Arizona. There’s a feeling of excitement, of real

awe, what the syphilis riddled German philosophers used to call the sublime, in

his landscape scenes out here. Because, and only because, he published his

photographs as postcards, we tend to brush aside the idea that such a person

could feel any spiritual empathy with the land. I think you could only take a

photo like this if the scene moved you. I’m prepared to guess that Frasher

waited until he thought the sunlight fell just where he wanted. Also, he found

the precise position that emphasised the strangeness of these geological

wonders. I say that, but it might be worth knowing that Frasher is standing at

the edge of Route 160 when he took this. Maybe he was driving past and got

lucky, or just as possible, he’d driven down this road so often that fifteen

miles away, he glanced up at the sun and realized that if he planted his foot

on the pedal he’d get here just in time.

This

is just the kind of view that Ansel Adams acolytes would dismiss as average,

yet for their opponents it proves the very point that Frasher is more

interesting. Perfection and feeling are seldom synonymous. One guts the other.

How would Mr Adams have dealt with this scene? We know the answer almost

immediately. Firstly he would have emphasized the contours in the distant

mountains, and then the snow on the even more distant peaks. But what does

Frasher draw our attention to? Well, ‘Mushroom Rock’ for a start, but also the

road. This is as much a photograph of the experience of driving across Death

Valley as it is of an unusual geological feature. What the Adamites don’t get

is that the snowy peaks work best subliminally. They don’t matter so much as

the two odd squares on road improvement just below the mushroom. This is as

much a photo of what it means to drive across Death Valley as Death Valley

itself. Anyone who has been fortunate enough to experience a road trip across

the American southwest knows that the true wonders lie in the glimpses, not the

studied observations. Of course Frasher stopped to take this photo but it was

sold as a reminder to travellers of what they had seen and what they had

missed.

Frasher’s

postcard of North Virginia St, Reno, bears an uncanny resemblance to several

taken by Lawrence Engel of the Nevada Photo Service about the same time. We

could say the differences are so slight we ought not bother with them. This is

Reno in its heyday. I doubt anyone visiting today would disagree.

Interestingly, (I say, having only just realized this) the absence of casino

and club signs indicate this was taken either before or just at the time that

Nevada legalized gambling. The effect of that upon Reno’s streetscape was dramatic.

These days North Virginia St isn’t even a shadow of its glory days; it looks more

like a bunch of developers dumped a bloated corpse on the street and walked

away. Still, the point here is not to remind ourselves of legitimated criminal

behaviour but Burton Frasher. My feeling is that Frasher may be ignored by the

standard histories but those of us who suspect there is always something left

out or overlooked will discover his work and in the process reinvigorate a

tired story. Anybody who believes the story of America’s landscape photography

has been told hasn’t looked hard enough.

|

| FRASHER'S FOTOS |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Add comments here