Five real photo postcards from France, 1910 to the 1920s

“In Paris everybody wants to be an actor; nobody is content to be a spectator.”

Jean Cocteau

It’s 1919. The war is over, the economy is crawling back, a vast array of amusements such as cinema, cameras and especially cars have become accessible to just about everyone. It’s time for a holiday, so where do you go? New York, capital city of the 20th century, or Paris, where people in the know swear the real action is. Between 1920 and 1925 some 300 000 Americans moved across the Atlantic. Paris was cheap and it made the U.S look as much fun as afternoon tea with someone’s old, tired and prudish aunt: all those wild stories coming out of music halls like the Folies Bergère were enough to make any civilized adult pack their bags. The stranger thing is that while Americans thought of Paris as the centre of all that was risqué and challenging, they could see a contortionist pull off the same feat as the woman above for a couple of pennies at any small town fairground. She probably performed under a French name and had an invented background that included stints at the major Paris theatres. What she lacked was glamour. No idea who this woman is though she looks tough enough to handle Paris and America’s mid west carnival scene without a blush.

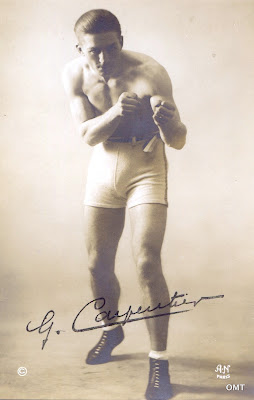

Read some books about Paris in the 1920s and you could be forgiven for thinking the city was inhabited only by a half dozen Americans on the cusp of fame and a handful of poor and dissolute European artists. Easy to forget too that during his period in Paris, Hemingway was an unknown or that Joyce didn’t need all of his fingers to count the people who read Ulysses. Much more famous and more emblematic of Paris was Georges Carpentier, war hero, world light heavyweight champion, and singer, dancer and actor with a straw boater and cane. Maybe Hemingway could write a better sentence but Georges had his measure in all the arenas of his imagination so it’s a good thing they never became friends. It wouldn’t have lasted. The point about Carpentier was that he could not only punch a man’s lights out but he knew – at least this was the impression - the right wine to go with the cheese. That was a no-no in America where a man could do one or the other but ability in both was suspect. Maybe that was why so many Americans worshipped Carpentier. He represented something that was missing back home.

It took guts to face Jack Dempsey in the ring, but was that more terrifying than crossing the English Channel in a flimsy wooden aeroplane>Flying at 72 kph, which was, we shouldn’t forget, extremely fast for that time, Louis Blériot made the crossing in just over half an hour on the 25th of July that year and became an international hero. Actually, his most enduring achievement was the development of the monoplane but his design for the wing warping would send him into court against one of America’s most enthusiastic litigants, Wilbur Wright. As with most of his cases, Wright would lose – well, technically he’d win but most countries ignored the judgement – though he held up development of Blériot’s designs for a couple of years. In the meantime the French could continue celebrating Blériot’s groundbreaking (if that’s the word) flight with postcards like this, which is an excellent example of photomontage.

A flâneur wandered the streets without any apparent aim but a true boulevardier didn’t travel so far; from the office to the bistro and then maybe another bistro. Boulevardiers needed a job but it was as important to look like they didn’t. Sitting at a café, one didn’t glance at a watch and exclaim that one had been required back at the office ten minutes ago. Rather, one assumed that late was late so ten minutes was no different to one hour. Besides, that lunch extending through the afternoon could be centred on important business. It was necessary to be seen, after all, back in the office you were hidden from the world, as anonymous as the lowest clerk. A J Liebling returned from Paris in 1927 and became one of New York’s celebrated boulevardiers; strolling along Broadway was business as he picked up stories and tips for his New Yorker articles. Back in their natural home, boulevardiers were about to lose their aura of respectability. In the 1930s well dressed idleness was a bad sign.

|

| LES ANNEES FOLLES |

What a fun read and a marvelous post. In fact, this is a perfect post - one that takes you on a little journey and leaves you knowing a lot more than you did, but also makes you curious to know more. Very nicely done.

ReplyDeleteThe first picture made me want to try doing the splits, but I know better. I love your comment about Paris in the 1920s...so true.