The photographs of Lehnert and Landrock

“If I had been a moderately good otter I suppose I should get back into human shape of some sort; probably something rather primitive – a little brown, unclothed Nubian boy, I should think.”

Saki: Laura

Dixieland bands - white, middle aged men wearing straw boaters and candy striped shirts - are a travesty of jazz. They take all the necessary elements yet somehow leave out the soul. The Lehnert and Landrock Company were the Dixieland artistes of Oriental photography. From 1904 to the 1930s they exploited the image of Egypt, from its antiquity to the eroticism of the veiled Muslim, the sunless medieval jumble of the cities to the simple dignity of the peasant, and made it accessible. Whether we accept their photographs as realistic interpretations or reject them as colonialist stereotypes, we are familiar with their Egypt. We saw it in Raiders of the Lost Ark and just about every other film set in Egypt before World War 2. There are no florid European men in white linen suits and panamas or straitlaced wives of British diplomats loosening their bodices in Lehnert and Landrock photographs, but in a way they are full of them. In a way, when we look at Lehnert and Landrock photographs, we become either of those two types. Much more than the earlier, monumental landscapes of Francis Frith or Maxime du Camp, Lehnert and Landrock’s impressions infused the European imagination for most of the 20th century.

Rudolf Lehnert was the photographer, Ernst Landrock the business manager. They met in Switzerland in 1904 and later that year moved to Tunis to open their first studio. In 1924 they relocated to Cairo, two years after Howard Carter had uncovered Tutankhamen’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings. If Carter’s discovery had no influence on the company’s decision to relocate, the move was fortuitous. Tourists were returning after the hiatus imposed by the war. Popular novelists like Agatha Christie and John Dickson Carr took murder out of the English manor and set it in the desert. Art deco designers rediscovered Egyptian form. Lehnert had a gift for depicting Egypt the way westerners wanted it to be.

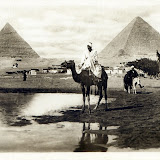

Tourists went to Egypt to have their expectations fulfilled. They came to see antiquity and exotic landscapes. No one really went there because the political situation was interesting. In a typical Lehnert view of the pyramids they are placed in the background, often slightly out of focus. The foreground is given to an Arab, his camel and a date palm. This was about a complete picture of Egypt as anyone wanted. To ask for more would have been greedy, to give it would have risked raising questions; ‘what’s that doing there?” “Are there really such things running around Giza?” Naturally, the people in a Lehnert and Landrock photograph are poor but happy, and look remarkably healthy.

Today the image of the veiled woman evokes negative connotations; fundamentalism, oppression, terrorism. In the 1920s it seems a more important question was what lay underneath her garments. Lehnert and Landrock told us. Their nudes remain their most sought after images. The market back in Europe may have been select but from the sheer number of images still circulating it was also insatiable. Of course, the Orient always had that allure; Flaubert’s Egyptian journals from the 1850s amount to a brothel crawl with occasional, obligatory investigations of the ruins, and he was hardly the first to visit with more than history on his mind. Lehnert and Landrock also catered to the pederast market. Androgynous semi-naked boys lounging against doorways were a specialty. The image on view in the gallery, “Good Friends”, is borderline. It could pass as a shot of typical native boys but it could also be an invitation to ageing European males of a particular inclination.

When Edward Said published Orientalism in 1978, he made no mention of Lehnert and Landrock but he gave their nudes an intellectual credibility. Once they had merely been exotic soft porn. Now people could buy them as artifacts of cultural analysis their value shot up. Said might say that has only confirmed his argument that all westerners were imperialists but what was he expecting? Thanks to his book, exhibitions and catalogues of orientalist art (particularly of the academic variety) had a new cachet.

Lehnert and Landrock published an enormous number of images in several formats, from archival fine art prints to lithographs, photogravures, postcards and miniature snaps. The fine art prints (particularly the nudes) can sell for several thousand dollars. Postcards and snaps can easily be found in European antique stores and junk shops. The images in this post include a heliogravure, medium format prints, postcards and snaps.

|

| DEATH ON THE NILE |

Great photos. And I just started re-reading the Cairo Trilogy.

ReplyDelete