In the 1920s modernist principles began to creep into commercial photography. The old axiom that the photograph was a statement of truth gave way to the concept of representation. Shape, form and texture mattered, also the idea that the message could be abstracted using lighting and angles. Political leaders looked more impressive if the camera pointed up to them, thinkers seemed more profound and enigmatic if half of their face was cast in shadow. A photograph was not of a world famous author but of genius, distilled. The nude was no longer the subject, eroticism was. Photography was accepted as a type of fiction.

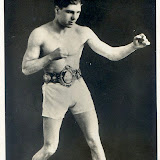

The boxer was a perfect subject for photographers. His uniform was his semi-naked body, and coiled into a fighting pose against a stark background, its minimum of information delivered a complete image of physical strength, courage and skill; the virtues all young boys were expected to aspire to.

Boxers were gods, local gods, mind you. One could be worshipped in Whitechapel yet unheard of in Brooklyn and the devotion was assuredly sectarian. Ted “Kid” Lewis was also called the Aldgate Sphinx but the faithful knew his real name was Gershon Mendeloff and so far as they were concerned he was fighting for more than the simple pleasure in it. Promoters understood this all too well. Set a Dublin Catholic against a Glasgow Protestant and you had more than a boxing match, you had a metaphor, and a full house.

Ted ‘Kid’ Lewis, No 10 from “Sporting Champions”, available with ‘The Champion”, April 1st, 1922

In popular imagination a champion embodied the canard that a boy could literally fight his way to the top of the heap. The qualities that got him there involved discipline, character, pluck and desire. Small wonder that in so many films from the 1930s and ‘40s involving boxing, a priest hovers about to remind the boy, and the viewer, the wayside is only a misstep away.

Like the boxer, the actress needed nothing more than her physical presence for the photographer to start constructing a myth. The intention was to infuse her image with glamour. It was irrelevant if she spoke with a broad Midwest twang and assumed a book was something a judge threw. A hairstyle, a gown and some basic lighting could transform her into a creature of such elegance and sophistication to make, as Raymond Chandler put it so succinctly, a bishop kick a stained glass window in.

Ginger Rogers, No 16 from “Modern Beauties” Third Series.

No one ever required an actress to show character off screen. Her image in front of the camera was sufficient as her virtues were entirely physical. Indeed the classic legend of the actress’ path to glory in is contradistinction to that of the boxer. He fights. She is discovered, plucked from her job at the milk bar and miraculously transformed into a star. The Hollywood priest reminded the struggling fighter to dig deep into his soul to bring out his greatness. She, on the other hand, had “it”. Frankly, when all that was ever asked of her was that she look good under a klieg light, it was ungrateful that she’d demand the right to a personality.

Modernist photography was only interested in the surface anyway. Genuine modernists cared nothing for the substance of their subjects’ lives. How could they? To depict the squalor most boxers came from, to suggest that they fought professionally because it was a skill they picked up alongside petty thievery, was to spite the imagery of magic and dreams commercial photographers built their careers on. That would be like a Hollywood producer insisting that true love was a sick, cynical joke. And who wanted that? Not the audience; the man gazing lasciviously at the magazine starlet’s thighs while his dumpy wife pottered about the clutter of the kitchen, or the girl who imagined that if she only wore that gown her life would be fulfilled. Not their subjects either, whose whole purpose had been to escape the ghetto or the barren little town in the first place. The new modernism showed photographers how to create mythologies everyone wanted.

Cigarette cards had been around for a while but beginning in the 1920s, companies began including real photos. For a shilling a smoker could buy a pack and have a small piece of authentic modernist art included. The buyer wasn’t expected to think about art of course but that pantheon of deities, the screen goddesses, the lords of the ring who, in their portraits at least, were mortal, yet somehow above the fragility of commoners.

Most modernist artists scorned populism, and among those who didn’t many failed to make a tangible connection with an audience. Intentionally or otherwise, their manifestos and theories alienated the people whose thinking they were supposed to transform. Paradoxically, it was left to commercial photographers to dispense with all but the superficial appearance, bring it into the home and make it mainstream.

|

| THE PRIZEFIGHTER AND THE LADY |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Add comments here